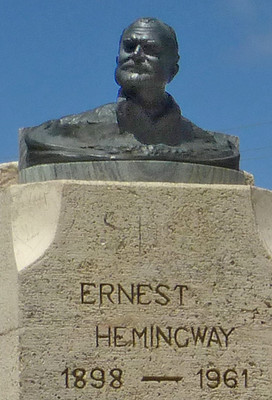

I really had just one "must do" agenda item for our week in Havana. A visit to the Ernest Hemingway home and museum, Finca Vigía, just a few miles outside of Havana.

Ernest Hemingway is permanently linked to Cuba through his Nobel Prize winning book, The Old Man and the Sea. I first read this book in the 1950s, perhaps when I was still in grade school; I had little appreciation for the style. A few years later, I stumbled onto "Papa Hemingway," A. E. Hotchner's 1965 memoir of the fourteen years he was interviewer, editor, screenwriter and friend of "Papa." Hotchner's book is still a "must cite" resource for anyone researching Hemingway.

A great writer in his own right, Hotchner penned a few thoughts about Havana and the finca in 2004 in a new preface to his book, after returning to Cuba after a 44 year absence.

I have returned to Havana, the first time I have been here since July of 1960 when I had stayed at Hemingway’s finca in San Francisco de Paula, just outside Havana, helping him extract 40,000 words for Life magazine from the 108,746 words of his just-completed manuscript, The Dangerous Summer. As I go from the airport to my hotel, I am struck by the fact that Havana is a city frozen in time. The automobiles are the same ones that were on the street when I left, the same Fords and Chevies and Pontiacs and de Sotos, and for all I know the Buick station wagon we are passing, with its fins and three-circled engine hood, may be the very one in which Ernest drove me to the airport, forty-four years ago. A city frozen in time, but slowly succumbing to the ravages of time.

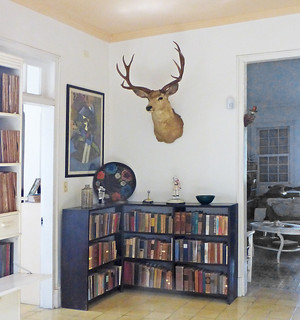

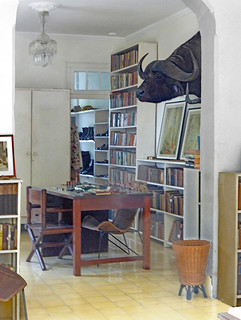

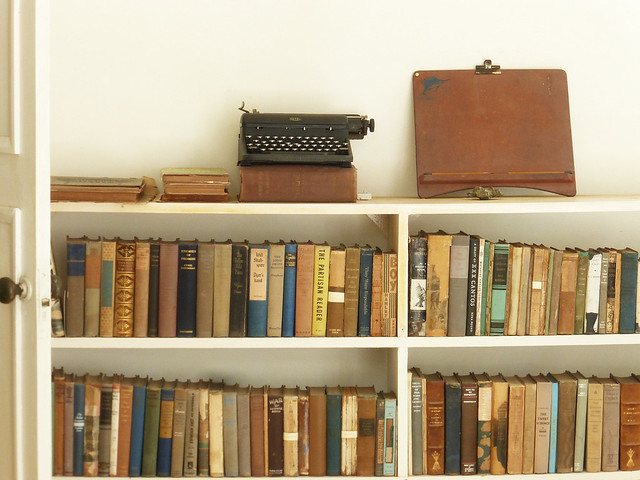

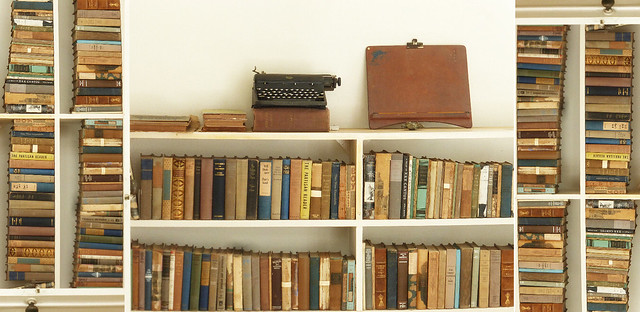

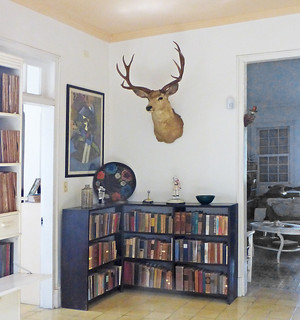

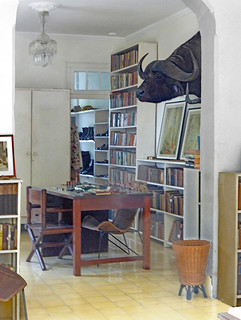

Ernest’s beloved finca still stands imposingly on its hilltop, and the interior is precisely as he left it when he abandoned the house in the fall of 1960. All his books, clothes, liquor bottles, guns, animal heads, just as they were, but the old finca is suffering from neglect and a hostile climate. The roof leaks and the ceiling of Ernest’s bedroom, where he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea standing at a portable typewriter mounted on top of a bookcase, has been shored up with floor-to-ceiling supports. The foundation under Mary Hemingway’s bedroom is being eroded, and the invaluable books, autographed and annotated, are in various stages of disrepair.

But Ernest’s presence is very much in this house that Mary donated to the Cuban government, which now operates it as a museum. I sit down in the living room armchair which I had occupied so many times after lunches and dinners when Ernest would discourse about adventures and writing and acquaintances and sports and the many subjects that intrigued him. I could sense him beside me in his favorite armchair, a whiskey and lime in his hand, contentedly telling me how some of the Brooklyn Dodgers, when they were down for spring training, would come to the finca for a night of boozing and brawling.

I re-read Hotchner's book (Kindle edition) just before we left on this trip.

Our guide for the first two days in Havana, Abel Martinez, was happy to accommodate our desire to tour the Hemingway museum the next day, and even phoned to be sure that it would be open on Monday. He suggested a different car, noting that his neighbor, Billy, had a convertible and could be our driver - if Billy had or could find gasoline - a big problem in Cuba nowadays.

At 10:00 AM the next morning, Abel and Billy were waiting outside for us in a sparkling 1949 Chevrolet Deluxe convertible. He opened the hood for us to check out the 216 cu. in. OHV six-cylinder original engine!

We were quickly on the road to Ernest Hemingway's Finca Vigía (Lookout Farm) located about eight miles southeast of the Capitol building in Old Havana. Although only a short distance from the center of Havana, we passed by a bit of farmland with banana trees, along with occasional industrial buildings en-route.

Turning off the main road, we pass quickly through the small village of San Francisco de Paula, heading up the hill on a tree-lined drive to arrive at the gate of the museum property. The large limestone villa dates from 1896. It was purchased by Hemingway and his third wife, Martha Gellhorn in 1939. They divorced in 1945 and Hemingway married Mary Welsh in 1946. The couple lived here until 1960 when the property was appropriated (or, as the Cuban government puts it, "donated") for the people of Cuba. It is preserved as a museum and tourist attraction.

The stately home comprises about 3700 square feet on a single level with almost a hundred foot width at the main entrance.

Famous House Plans on Facebook has what appears to be an excellent floor plan of the finca.

Visitors are not actually allowed inside the home. The windows and doors are open, and we walked from one window and door to another peering inside and taking photos. Looking through the house, you see the tourists on the other side.

We will follow the layout moving counter-clockwise beginning with the 42' x 17' Great Room. Here, the room is pictured with a glance to the left and the right. The person you can see inside the house is a docent.

A few details from that room.

Next is Hemingway's bedroom. The second picture shows the whole end of the house, looking through his study and into the walk-in-closet where he left quite a bit of footwear.

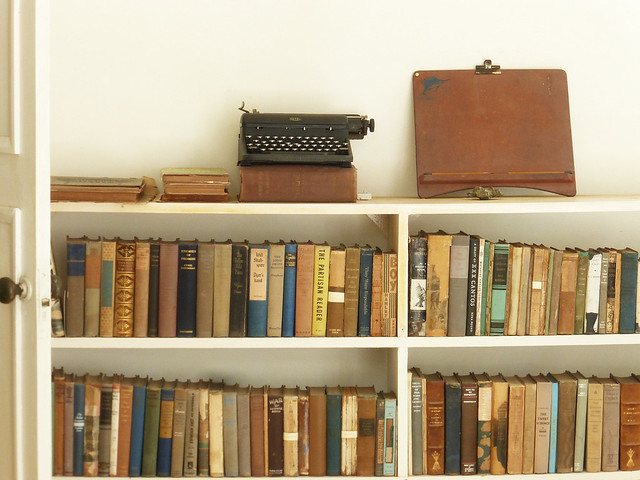

But wait, let's take a closer look at that bookcase to the right of the bedroom entry door. Note the typewriter? This is where Hemingway preferred to write from a standing position.

What about the books, in that bookcase that served as an author's workstation? Can we see any titles on these books in Hemingway's bedroom? Yes, we can easily read a few of them. (I flipped them over so you can easily scan the titles, when necessary)

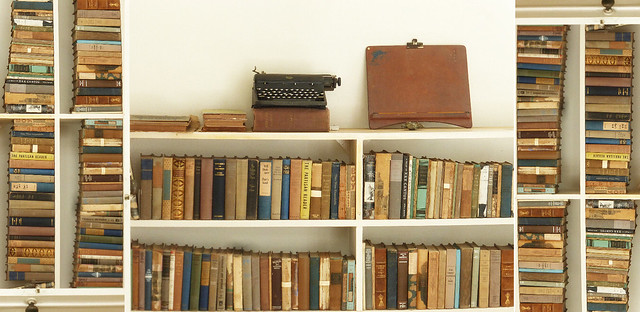

Some of the sources that discuss the finca suggest that there are 5,000 books on the shelves. Hemingway was a voracious reader, once suggesting in a letter that he averaged about one and a half books per day. "He never got rid of anything," according to Mary. Since he read extensively in bed and worked at the typewriter in his room, I browsed the titles in the picture.

I found a few in there of some interest.

Oil, Australia and Oregon.

Boy, by James Hanley, 1931-34

Brief life of a 13-year-old stowaway at sea.

The story of the author and his wife's two-month safari in East Africa in the 1950s.

(an interesting find!)

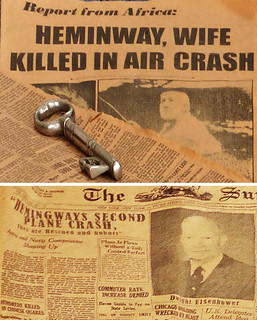

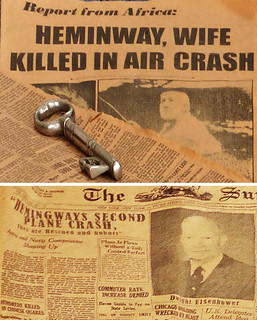

Before we leave the bedroom, note the two newspapers on the bed from late January, 1954, reporting the deaths of Ernest and Mary in a second plane crash in Africa after surviving a crash on the previous day.

Continuing around to the back of the home, we take a look at the spacious library.

Of course, my eyes moved quickly to the speaker enclosure in the corner. "Is that a Klipsch," I wondered? Paul Klipsch was to become as well-known in audio circles as Hemingway was in literary circles. Hemingway was deeply into a variety of subjects. I hadn't read anything about him being an audiophile, though. (The eccentric Paul W. Klipsch manufactured his speakers in Hope, Arkansas where he was the town's most notable citizen up until ...)

The first Klipsch speakers were available via mail order.

Moving on to the guest room, note the Tower (Sears house brand) 35mm slide viewer and the slide projector - more high tech tools from the early 1950's

Outside, we climbed the three story tower via the outside staircase. Hotchner says that Mary had the tower constructed to get the complement of thirty cats out of the house - and to give Ernest a more becoming place to work than in his bedroom office complex. It worked for the cats, apparently, but not for Ernest. From Hotchner:

The top floor of the tower, which had a sweeping view of palm tops and green hillocks clear to the sea, had been furnished with an imposing desk befitting an Author of High Status, bookcases, and comfortable reading chairs, but Ernest rarely wrote a line there—except when he occasionally corrected a set of galleys.

The view is marvelous. You can easily see the golden dome of the Capitol in the distance.

From the house, we made our way down past the cock-fighting ring and the swimming pool to the former tennis court that now has a roof above it and serves as shelter for Hemingway's boat, the Pilar. Here it is, in mahogany, teak, black and red - with a United States flag on the stern.

We didn't see many of those flags on our stay in Havana. The Pilar was constructed by The Wheeler Shipyard Corporation of Brooklyn, N.Y. in 1934. Thirty-eight feet long, the boat is a classic design and a duplicate was constructed in 2020 by Wheeler family members.

We made a thorough inspection of the boat.

The walking path between the tennis court and the main house is lined with palms. The house is surrounded by lush tropical vegetation.

Hotchner reported that eighteen varieties of Mangoes grew on the slope between the main gate and the house. As we returned to the house, one of the gardeners handed Abel a couple of mangoes.

We paused to admire the nearby terrace. An invitation to Finca Vigía must have resulted in a memorable event for anyone fortunate to receive it during the '50s.

We walked by the large guest house to visit the souvenir shop where I found a nice straw hat at the lowest price I had seen in Havana. We purchase some lemonade and a Coca Cola before leaving.

The Staff at Finca Vigía

A home like Finca Vigía doesn't run itself. What kind of staff was required to handle this operation? Once again, Hotchner gives us the story. There were usually ten employees.

The staff for the finca normally consisted of the houseboy René, the chauffeur Juan, a Chinese cook, three gardeners, a carpenter, two maids and the keeper of the fighting cocks.

More about Finca Vigía and Hemingway - Some Resources

The New Yorker December 21, 2017

Smithsonian Magazine October 10, 2019

Includes a photo of a bare-chested Hemingway sitting in one of those Chintz fabric chairs in the great room. Also a photo of Hemingway with Fidel Castro.

The Final Days of Ernest Hemingway

The Castro revolution succeed in overthrowing the corrupt Batista regime on New Year's Day of 1959. In 1960, Cuba began to nationalize American businesses operating in Cuba. By July of 1960, Hemingway realized this would be his last year at the finca. It was doubtful that he could get his art collection out of the country.

How much the loss of the finca factored in to his mounting depression is unknown, but the depression and mounting paranoia led to a series of electroshock treatments at Mayo Clinic. The resulting loss of memory and inability to write led to suicide on July 2, 1961.

Final Thoughts

Ken Burns put together a six-hour documentary on Ernest Hemingway in 2021. I have not watched it yet but here is a review published in America magazine by the Jesuits. It is titled simply, "Ernest Hemingway was a brilliant writer and a terrible person. Discuss." That title sets the stage for modern day sentiments such as this:

So much of what Hemingway loved and valued is considered distasteful in

our current culture: his admiration for the art of bullfighting, his

passion for big game hunting (the photographs of dead lions and now

nearly-extinct rhinos—a smiling Ernest posing above their lifeless

carcasses—are hard to look at). And yet from his childhood Hemingway was

enchanted by the natural world, and as an adult he admired the beauty

and power of wild animals, the bravery of the bull. He wrote about them

with extraordinary sensitivity and precision. “The pleasure in killing,”

Tobias Wolff admits, “is a mystery to me.”

But it is worth remembering that when Ernest and third wife, Martha, moved into Finca Vigía in 1939, that year was less than half-way between the Civil War and the present. The Atomic Bomb had not yet been developed, much less used. Hitler had only recently invaded Poland and the Holocaust had not begun. Fidel Castro was thirteen years old. It was a very different era.

Are there more pictures? Of course. Click on almost any of the photos above to enlarge and find your way into the Flickr Photo Album for these pictures. Or just click here.

===============================================================

UPDATE: May 18, 2023

While looking through my photos and assembling the above blog post, I had a hard time reconciling the condition of Finca Vigía that we saw with the description of its condition in the new preface to "Papa Hemingway" in 2004. It turns out that the finca has gone through an extensive renovation by the National Council of Cultural Patrimony (CNPC) of the Ministry of Culture.

The renovation, in 2004-6 almost completely rebuilt walls, floors and ceilings. It was described in some detail, along with pictures at a CNPC website - but that apparently has disappeared. Fortunately, the "Wayback Machine" captured most of the material. You can visit the renovation description including thumbnail photos at this link (the photos take a while to load). The picture below is just a "teaser."