Many of the exhibits in the Baron Empain Palace describe the Baron's project to build the new town of Heliopolis beginning in 1905. As we headed up the marble staircase to the "First Floor," we noticed a large panel displaying sixteen drawings and photos relating to the nearby area. I took a few photos but we didn't have a chance to read all of the material until a few days later.

The ancient town of Heliopolis, seven miles northeast of Cairo, had a rich history going back thousands of years before Baron Empain arrived. This 1882 Birds-Eye View of the Cairo area shows the surrounding area.

Empain and his business partner, Boghos Nubar Pasha, reportedly acquired their 2500 hectares of desert land (almost ten square miles) for less than 6000 Egyptian pounds in 1905.

The baron was cautious about beginning construction on the site. He contacted the Belgian archeologist, Jean Capart, to explore the surrounding area for burial grounds associated with the ancient Heliopolis. Capart failed to find any evidence and construction was soon underway.

The Empain-Pasha concession consists of the triangular shaped property shown in the document above and below. The lower photo highlights a few of the features mentioned in various accounts of the archeological exploration for graves and artifacts.

There are some amazing photos of Heliopolis under construction, of the 1910 aviation meet at the nearby airfield and of the city as it grew, but little evidence of what must have been a magnificent ancient city.

A 2019 article in Archeology magazine describes the scant remains of the ancient city:

At its peak around 1200 B.C., the holy site was marked with dozens of colossal obelisks. Heliopolis was known far and wide in antiquity. Called "On" in Hebrew, the city is mentioned multiple times in the Old Testament.

... Yet today, Heliopolis is virtually unknown. After almost two and a half millennia of continuous worship there, the importance of its temples declined. By the second century B.C., the city was abandoned, for reasons archaeologists are still trying to discern. It was subsequently plundered and stripped of anything that could be burned or reused. Beginning in the late Roman period, nearly all of its limestone architecture was carted away to build Cairo, leaving little to see above the surface. Over time, most of the city’s obelisks were removed, carried off first to decorate Alexandria, and then to Rome, Paris, London, and even New York (see “The Obelisks of Heliopolis,” page 30). Only one still stands at the center of the site, a 68-foot-tall red granite monument erected by Senwosret I around 1950 B.C. that juts out of the ground in the impoverished Cairo neighborhood of Matariya like a hieroglyph-inscribed spike. By the 1800s, Heliopolis had all but vanished under the silt that builds up during the Nile’s annual floods. It was buried under farm fields on the outskirts of Cairo. What was left of Heliopolis is now covered by between six and 20 feet of soil and debris. “It’s extraordinary that one of the most famous cities of the ancient world is now a ghost of a name,” says Stephen Quirke, head of the Petrie Museum at the University of London. “It’s a black hole in our knowledge of ancient Egypt. Heliopolis is the great site.”

One can only imagine the view approaching Heliopolis in ancient times with the sun reflecting from the gold covered tips of those dozens of obelisks.

As for the modern city, French historian Robert Ilbert notes the rapid growth in a 1984 publication:

The first buildings began to rise in 1908, at the same time as the first tram route to Cairo was being opened (a distance of about 10km from the centre of the city). Also during this time the desert had blossomed into an oasis and there was speculation about moving Egypt's first aerodrome, which Empain had decided to build on his concession, further away. Although there were barely a thousand inhabitants by the end of 1909, by 1915 the figure had already risen to 6,210, increasing to 9,200 in 1921 and jumping to a high of 224,000 in 1928

This photograph from 1932 found in the United States Library of Congress, shows the airfield in the foreground with the still isolated suburb nearby. The hippodrome and horse track are partially visible at the upper left.

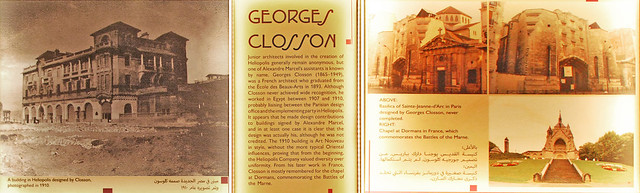

At the top of that marble stairway mentioned a few paragraphs above, we found a series of exhibits that among other things includes some of the architects who deserve special credit for their work on buildings in the new Heliopolis. (click to enlarge)

The comprehensive planning of Heliopolis provided space for all levels of society and, in fact, the town drew a widely diverse population. Historian Ilbert describes the character of the population:

Viewed demographically, the general composition of the new town shows that, on the whole, the population represented was typically Egyptian right from the start. At least half of the inhabitants were local including, in 1925, 20 per cent Europeans (in particular Italians and Greeks) and a large number of Levantines (about 30 per cent). However, from the standpoint of religions represented, the figures obtained in no way compare with those of the Egyptian average (the Christian element, for example, being greatly over-represented).

Socially, Heliopolis was always stamped with the image of the ruling class. The large numbers of Egyptian officials were due at least in part to the difficulties encountered by the Company between 1907 and 1911, when the two-oasis project had to be abandoned, and which resulted in accommodations being offered to the government at very low prices in order to fill the new buildings. But this setback was once more the promise of success, marking the transformation of a tourist city into a real town. In addition, the design of Heliopolis with its variety of buildings attracted Egyptians of all classes and the often considerable financing opportunities made available enabled purchasers to find in Heliopolis what they could not find elsewhere.

Thus it was that the new town came to be used as a stepping stone by the new bourgeoisie, an important factor to be considered since it partly explains the success achieved by Empain among the new middle classes in Egypt during the 1920s. To move to Heliopolis meant, in a way, integration into a new western pattern of living without, however, "going over the border" into an excessively homogeneous, completely foreign quarter. The slightly affected architecture of the town - oriental even if in pseudo-taste - projected the image of a "modern" type of town but, nonetheless, "Egyptian" in character.

A few buildings that were part major parts of the Heliopolis project deserve mention:

The Heliopolis Palace Hotel deserves special attention and you can find that in this 1998 article from the Cairo Times.

There is also a page of the original architect's drawings for the Baron's palace, "Villa Hindoue," among the exhibits.

For those of us who purchased tickets to the rooftop, there is one last stairway, and it is a gem.

Of course, the view from the rooftop is spectacular.

Details in that picture are easily missed. For example, there is a streetcar, the Baron's ticket to success, just across the street. That building in the foreground is the Hussein Kamel Palace - now an innovation hub. In the distance, continuing down the street on the left side, is the dome of the Heliopolis Basilica. Missing from the photo, off to the left side at the same distance as the basilica is the Palace Hotel, now one of the Egyptian Presidental palaces.

There are numerous interesting architectural details on the rooftop. Click on any of the pictures below to go to my Empain Palace Flickr album and browse more of the details.

We didn't begin to see enough of the area surrounding the Baron's palace. The modern suburb of Heliopolis and the nearby ancient obelisk will be a high priority on our list of sites to explore next year when we return. By that time, I hope to put my hands on a copy of this book published by American University in Cairo.

No comments:

Post a Comment